What Lies Ahead - Telecom outlook and future trends

The Indian telecom landscape is likely to undergo a significant transformation in the coming years. Not only is consolidation on the cards, but tariffs, revenues and costs are also likely to witness a change. 3G and mobile number portability (MNP) are also likely to be introduced. Leading industry analysts give their views on the sector's future outlook...

Kunal Bajaj: The entry of new players has been good for the industry in some ways. It will force consolidation to occur in the industry at a faster pace. On the negative side, the total value of the industry may come down. However, the sector will emerge stronger as it will be forced to innovate on the value-added services (VAS) side and look for alternative ways to keep the same levels of revenue and earnings before interest, tax, depreciation and amortisation (EBITDA) margins. I am actually slightly conservative on the average revenue per minute (ARPM), at least for the new entrants – it could be below the interconnection level of Re 0.20 if they are willing to invest for the sake of gaining market share.

Shubham Majumdar: In the short to medium term, which is over the next two years, we are looking at absolute revenues declining and flattening out for the overall industry. It is important to note that the subscriber addition numbers that keep getting reported are actually SIM additions, and the extent of dualor triple-SIM usage has been increasing significantly in the industry.

Assuming termination charges don't get reduced, ARPMs may reduce from Re 0.56 to about Re 0.47 per minute over the next fiscal year, and then potentially settle closer to Re 0.40-Re 0.42 levels. This kind of ARPM decline will not be offset by the growth in the minutes of usage, resulting in flattish revenues. The impact of this will be different on larger incumbents such as Bharti that have a large rural coverage (since the price war will be on the urban front mainly). However, the smaller operators will feel the real pinch, and I believe that margin declines in addition to revenue declines will clearly be coming through as well over the next 12-24 months. Absolute profits of the industry will probably come down 20-25 per cent as a whole.

But over the longer term, the industry will again start registering good growth rates, especially if data services take off.

Romal Shetty: The entry of new players has brought down tariffs considerably, and with another three players coming in, probably by the end of March 2010, tariffs are likely to witness a further reduction, at least for the next six months. With respect to the average revenue per user (ARPU), it would typically go down even to the Rs 100-Rs 120 level. EBITDA margins will definitely fall by around 5 per cent to 10 per cent.

The overall revenue growth in the sector is going to remain flattish, though it will increase a little. This is because though subscribers will still be added, these additions are not going to be significant in the short term.

However, telecom has got into the economic life cycle of people and if, for example, the GDP increases by 9-10 per cent per annum over the next three-four years, then, despite the bloodbath of two years, India will continue to be a very attractive market in the long term.

Mahesh Uppal: One of the most important impacts of the entry of new players is the pressure on spectrum. If, for some reason, the supply of spectrum to existing players is going to be impacted by the entry of new players, then their infrastructure costs will increase to mitigate the shortage of spectrum.

In addition, the increase in competition is going to force prices down. The new players only have the option of competing on price for voice calls as the rest of the market is still quite undeveloped.

Operator revenues will also be impacted because when prices decline, market growth is expected to mitigate the fall in revenues. It will, however, never be significant given the fact that more marginal users are entering the market. Besides, the new operators are also a significant threat to the profits of the older players.

We currently have 12 licensed operators. How many operators will continue to remain in the next four-five years?

Kunal Bajaj: Having five big operators in India is probably the way we are going. However, I don't think the new entrants, at least the ones that have major international partners and government backing, are going to go away any time soon.

So essentially, in the next two years, we may see the beginnings of consolidation but until the Telenors of the world get the valuations they are looking for, based on the expected return on investment, they are not going to be so ready to roll over and get merged into the larger operators.

The merger and acquisition (M&A) regulations that the Telecom Regulatory Authority of India is considering will definitely help speed up consolidation. Things are likely to start in the next 18 months.

Shubham Majumdar: As a whole, we tend to somewhat oversimplify M&A outcomes. Clearly, these operators are large companies with prestige to protect in their home markets, with their global audiences, investor bases, and so on. So even though they look like they have no business case, they have done extremely well in other emerging markets.

M&As are not going to be easy. There are no obvious fits that I can think of at this moment. Promoter-driven companies always have other considerations to factor in, apart from hard economic realities. At the end of the road, they may just be left with 1-2 per cent market share, and we may see some of the players just hobbling along and not expanding. They will eventually die a natural death. However, it is not going to be fast, easy and simple.

Romal Shetty: Typically, five to seven operators can still survive in India because the country has a growing population with a propensity to spend. The incumbents will obviously have the advantage and probably stay on longer, but some of the new players are really big guys as well. So there may be mergers or they may stop operating in India. But, either way, after two years the new players will probably take a call on whether they want to continue in this market or not.

Mahesh Uppal: Over the next four-five years, six to seven players will be operational as the Indian market has been able to accommodate these many players in the past as well. But beyond that, there will be a problem. Even if the market is able to sustain the influx of these new entrants to some extent, eventually they will want to scale up. New players will not be content with being marginal players, and will either have to buy or be bought in the long run. Many of these operators are formidable players unlike the small-timers of the earlier days.

With respect to 3G licences, who can afford to not bid and of the ones that are bidding, how much will they bid? What will happen to those who bid and lose?

Kunal Bajaj: In the metro category, we are going to have an inordinate amount of competition. It is difficult to see who the top four-five players will be. 3G is indispensable for acquiring or retaining high-end subscribers. When there were four slots available for auction, some of the new players would have perhaps participated in the auctions, at least for the Category B and C circles. However, as there are now only three slots, it probably does not make sense for any of them to even go through this strategic hassle. They may bid for spectrum in the Category B or C circles. One can easily see the reserve price more than doubling for the winners in the Delhi and Mumbai circles, which now have two and three slots respectively.

For those who do not win 3G spectrum, it's not as if the game is over. If we consider a three-year horizon, 3G may not be the biggest differentiator. Looking at 3G subscriber projections, there will be about 100 million subscribers, as against a total potential of 800 million subscribers. So, from that perspective, there are still 700 million others that can be served. This still makes a reasonable business case.

Shubham Majumdar: I don't think there is any company that would not like to bid, because the reserve price comes back if the company fails to win any spectrum. It will boil down to strategic choices regarding capital allocation. Where is one's dollar spent better? Is it on building a 2G network, rolling out a distribution network and establishing one's brand name first, or acquiring a strategic asset that will roll out only over 10-20 years?

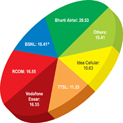

Incumbents such as Bharti Airtel, Vodafone Essar, Reliance Communications and Idea are best positioned to win 3G spectrum and pay the highest amounts. These players have the maximum amount of asset utilisation on their existing 2G networks. For them, the strategic uplift from 3G services is immediate and maximum.

The start-up operators will be better off investing their money and efforts on building their 2G networks and brands to begin with. As far as the bid amount is concerned, we are formally projecting the figure at $1- $1.2 billion for 3G spectrum in the 2100 MHz band for the player who wins the same in all 22 circles of the country. There are important issues: this is probably not the last opportunity to get 3G spectrum, since this is one of the government's big assets and will be used to bring in money through the door every two-three years. Over time, there will be more blocks of 3G spectrum that will be available. Also, spectrum trading rules will be put in place.

Romal Shetty: I believe that 3G spectrum will ultimately be priced much higher than the reserve price. There are five-six incumbents who would want it at any cost, and as there are only three slots, the bidding amount will only go higher. In India, 3G will mostly be used for voice services. I also believe that the new operators will bid for 3G as well.

Mahesh Uppal: Most players would eventually realise that being a pure vanilla voice player is not a good long-term strategy. Broadband or data services will have to form a significant part of their future plans. If that is the case, then only those people will not want 3G who believe that it's going to be too expensive because of the fewer number of slots available as compared to the number of players. The competition for spectrum, whenever the auctions take place, is not going to be trivial because there is an excess of demand over supply. The old GSM incumbents cannot let go of the opportunity to add spectrum because it is their spectrum supply that is most under threat, and in many cases they have exceeded the 6.2 MHz of 2G spectrum envisaged in their licences. It is, therefore, better for them to access additional spectrum by other means, that is, through 3G auctions. In addition, 3G is a highly spectrum-efficient technology that can support more voice and data, besides accommodating more players from the existing 2G business, thereby relieving the pressure. So a 2G player starved of spectrum will not let go of this opportunity.

For players who don't need the spectrum, there is still a competitive concern. The new players (new GSM players or an old CDMA incumbent now offering GSM services) will eventually compete with the older players and it is, therefore, in their interest to ensure that their rivals, the older players, don't get spectrum cheap.

In terms of the level to which operators will bid, it is highly unlikely that a national 3G licence will go for less than $1 billion. In the end, several players will have to do without 3G spectrum due to the scarcity of slots. Their market valuation will reduce, making them less attractive for a buy or for a merger.

What are going to be some of the key differentiators going forward?

Kunal Bajaj: We need to look at things from a customer viewpoint. There is a certain segment of customers that is going to move to 3G and is waiting for MNP. These are high-ARPU, highly selective customers who are aware of what services they can avail of. The major incumbents have already started customerattention initiatives, and are trying to create more individual relationships. There was an operator whose mass market launch strategy was totally focused on VAS. Unfortunately, it didn't necessarily bring in more consumers., though it did drive more usage amongst existing users of VAS. So, I think that the mass market strategy today is still about connecting the maximum number of subscribers and getting them on to voice.

Shubham Majumdar: An important consideration is the mediumto longer-term business models that we want to create in India. Until now, it was good to channellise all energies towards voice. These were obviously easy pickings for the market and larger operators, and growth came relatively easily.

However, we now have to think of customer segmentation and differentiated business models as well as look at niches and possibly data services as sustainable business models. The one-size-fits-all model that has been chased by every operator clearly does not differentiate between operators. We will need to have highly evolved business models with operators trying to differentiate and focus on more than just voice pricing as a differentiator. Data and 3G will give us that opportunity.

Romal Shetty: For any operator, there are four really important considerations: branding and positioning, network quality and coverage, customer services and differentiated offerings in terms of products. In the first two categories, there are operators that are comparable to the best in the world. However, when it comes to customer service, we are one of the worst and no operator is better than the other. In the past two years, we have tried to improve VAS, but unless very strong content is developed, offering these services will add no value. 3G is what will provide the applications. Right now, the impetus to develop strong content is not enough and that is why we probably don't have really differentiated products.

Mahesh Uppal: The quality of service (QoS) will, sooner or later, be the most important differentiator due to the large number of players in the market as well as some existing pressure to enhance the QoS. Another differentiator is the ability to support services other than voice. People increasingly buy more powerful phones and smartphones that require more bandwidth and stable networks. If an operator is not able to deliver, it will lose out on its lucrative customers, particularly if by then MNP is also in place. In addition, the range of VAS that an operator can support will also become important. There will be situations where people will choose operators on the basis of the services offered by them in addition to voice.

- Most Viewed

- Most Rated

- Most Shared

- Related Articles

- Prepaid Rules: Fewer takers for Postpaid...

- Mobile Banking: Opportunities and challe...

- Energy Management: A key challenge for t...

- Agenda for Change: Industry identifies t...

- Legal Concerns: Litigation against telec...

- R&D Focus : Need to promote indigenous p...

- Green Telecom: Business case for adoptin...

- Broadband Challenges: Key issues in serv...

- A Suitable Technology - Wi-Max or LTE?

- Tax Turmoil: Impact of the proposed retr...