Learning from China - Challenges and growth prospects for Indian telecom

-

The story of China's mobile market today is one of superlatives. China is the world's largest mobile market, with over 370 million subscribers. China Mobile is the world's largest mobile operator, with some 230 million subscribers. Even "niche" technologies like PHS – operated by fixed line operators China Telecom and China Netcom – have over 83 million subscribers in China, almost 18 times the number of subscribers in Japan. China's internet population will in the next few years overtake that of the US to become the world's largest. Broadband subscribers are already more than in either Japan or Korea.

It is easy to forget, however, that just 10 years ago China was a telecom backwater. In 1995, China counted a mobile subscriber base of only 3.63 million. Mobile phones were popularly associated with tycoons, given their connection charges of up to $2,000. Coverage was sparse. Fixed line connections involved waiting lists of over six months and charges of over $800. Commercial internet access was launched that year in China, but was available only to a privileged few, at painfully slow connection speeds.

China's achievement in transforming itself from backwater to world-leading market is something which other developing markets have studied with intense interest.

Foremost among these is India. Much as French economic planners in the 1960s and 1970s obsessively looked to Germany as their model "Outre Rhin" (across the Rhine river), an "Over-the-Himalayas" mentality is taking hold in India. A mix of envy at China's achievements, and fear at its potential implications in terms of manufacturing prowess, share of foreign direct investment (FDI) and access to capital, is palpable in India's business community.

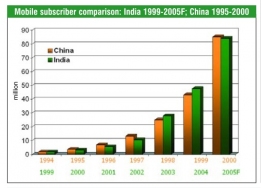

There are some good reasons for India to look to China. If we look at the past decade of China's mobile sector growth, there is a striking similarity between China's experience in the first half of the decade and India's performance in the second half. India in 2005, which is on track to exceed the 80 million mobile subscriber mark, looks very much like China in 2000 which ended that year with 85 million subscribers.

Now the question presents: Will India's market over the next five years grow at the same pace as China's over the past five years?

China and India: Some common characteristics...

In addition to the subscriber trajectory similarities, India and China share a number of common macroeconomic and demographic characteristics.

GDP growth rates in excess of 7 or 8 per cent per annum are the norm. Both countries are home to a population of more than 1 billion. Both count a large rural population of over 700 million. The pace of urbanisation, or of bringing telecommunications to this population in situ, has a large bearing on the future penetration rate. Both countries have already seen their mobile subscriber base surpass fixed line users.

China and India both have a strong youth demographic, each with over 100 million 20-24-year-olds. Among these, both countries graduate several hundred thousand engineering students per year, key to attracting technology FDI and establishing nascent technology companies.

...But the comparison cannot be taken too far

Yet there are a number of important macroeconomic differences. China's average GDP per capita of $1,269 is almost twice that of India's $638. This reflects in part the fact that China's urbanisation is more advanced, at over 40 per cent of the population to India's 28 per cent.

The differences in the two countries' telecommunications landscapes are even more striking. Due to regulatory missteps in the mid-1990s through the ill-fated policy of licence "circles", India suffers from a history of excessive carrier fragmentation. This is reflected in network coverage. At year-end 2004, only 22 per cent of India's population was covered by mobile telephony versus 92 per cent of China's. In terms of penetration, both have a lot of room for growth, with only 6 per cent of the population owning a mobile phone last year, versus 27 per cent in China.

In part, India's past regulatory mismanagement provides an opportunity for a more rational approach to drive sustained growth. The rationalisation of India's regulatory framework began with the 1999 New Telecom Policy (NTP, 1999) and has seen a series of important measures which have removed the brakes on the sector's development.

These include the removal of geographic restrictions on operators, the introduction of fixed-wireless local loop services, the introduction of calling party pays, unified access licences, an increase (to 74 per cent) in the ceiling on foreign investment, a universal service obligation policy to fund rural development and a proposed (but still uncertain) rationalisation of the access deficit charge (which has favoured fixed line operators to the detriment of mobile operators). The resulting consolidation and surge in new investment is transforming India's mobile market, giving grounds for optimism that the government's target of expanding network coverage to 75 per cent of the population will be reached within the next few years.

At the same time, the imposition of service taxes, licence fees and spectrum charges continues to weigh heavily on India's mobile operators. India levies a service charge of 10 per cent plus general sales tax (GST), in contrast to China's 3 per cent. Licence fee charges of 6-10 per cent and spectrum charges of 2-6 per cent are charged in India, versus 0 per cent and less than 0.5 per cent respectively in the case of China. In sum, Indian carriers labour under the burden of 18-26 per cent charges plus GST, versus less than 3.5 per cent in China.

This approach in part reflects the ownership structure of the two countries' telecom operators. In India, private capital plays the dominant role. In China, majority-state-owned carriers maintain a tight grip, made possible by a successful introduction to the international capital markets of limited equity stakes.

The tax burden doesn't end there in India. Import duty charges of 5 per cent are levied on handsets and 16 per cent on equipment. Critically, in India most telecom equipment is imported, eating up over 50 per cent of annual service revenues. While China also charges duties (of 10 per cent for handsets and 5-10 per cent for equipment), this has limited impact as most handsets and equipment are manufactured in China.

China – Challenges ahead?

While the Chinese subscriber base is much more advanced than India's, the country does face a number of looming challenges.

Although majority-state-owned, China's mobile carriers engage in intense competition which has driven down ARPU through a chase to the low-end subscribers. While in theory a duopoly, consumers in China typically have a choice of three mobile networks – the 2 GSM networks offered by China Mobile and China Unicom, and the CDMA network which China Unicom also operates – and in most towns a wireless local loop PHS network offered by the local fixed line carrier (either China Telecom or China Netcom) depending on location, to which some 83 million consumers have signed up. Handset subsidies offered by Unicom to drive stalling CDMA growth and calling party pays offered by the fixed line operators have dragged down ARPUs.

Saturation in urban areas also looms, with mobile penetration of over 80 per cent in Beijing and Shanghai.

A more serious challenge to the sector's future health is the high capital expenditures of operators. Chinese operators continue to spend much more than their international developing market peers on network expansion, mainly due to cosy links between local provincial operators and (mostly foreign) vendors. China Unicom spent 67 per cent of its revenues in 2004 on capital expenditures, and China Mobile 33 per cent. Despite plans to decrease spending, both operators have revised upwards their spending plans for 2005.

Also, while arguably India is moving to a more rational regulatory climate, China's regulatory framework has been somewhat adrift as the conflicting interests of the state in ownership, regulation and management manifest themselves. This has resulted in a series of botched moves, such as the government imposed a "two-network" strategy (linked to China's 2001 WTO accession) imposed on China Unicom, fuelling a subsidy binge which failed to deliver the expected subscriber growth.

China's murky 3G outlook also reflects the conflicting objectives of attracting FDI in manufacturing, promoting homegrown technology and concerns over the maturity of the market for 3G. As a result, China is engaged in an unending debate over which technology to adopt, when, and where – with attempts to promote TD-SCDMA meeting resistance from leading player China Mobile.

This reflects another area of potential concern, the increasing attempts by domestic interests to push local standards at the expense of international standards, delaying technology adoption. In addition to TD-SCDMA, these include the effort last year to replace 802.11 Wi-Fi with WAPI, and current efforts to promote domestic digital broadcasting standards.

A more intractable problem facing China is its continued attempts to separate networks from content as part of its efforts to maintain control of its media sector as a propaganda tool. The inability to achieve regulatory and network convergence of telecom and media will invariably hamper the development of wireless and broadband content.

India: Reasons to be cheerful

Despite the less favourable macroeconomic outlook, India can look to a number of robust growth drivers.

Voice tariffs in India are highly competitive at 3 cents per minute today, less than China's by a cent or so, and are likely to decline to 1 cent by 2007. While this poses challenges for operator profitability, the industry has responded with operators such as Bharti entering into innovative arrangements with vendors.

From the point of view of handsets, the outlook for India in 2005 is very different from that which faced China in 2000. In 2000, Chinese consumers paid an average sales price (ASP) of $260 for handsets, partly due to the "must have" status connotations. In India today, ASPs are already below $170, some $30 below current China ASPs, and the new phenomenon of ultra-low-cost handsets (ULCHs) offers tremendous promise. Handset manufacturers – with the active support of the GSM Association and other bodies – are promoting low-cost handsets to serve emerging markets, with India being a focal point. Motorola launched its first ULCHs at the $40 price point in April at the Cellular Summit 2005 in New Delhi and with its second batch in the pipeline, ULCHs are expected to reach $30 in the future.

Another bright point in India's favour is that telecom revenue growth of over 16 per cent can be expected this year, whereas China's telecom service growth rate has declined to match its GDP growth rate of 8-9 per cent. This gap is increasingly drawing the attention of international investors and telecom carriers, who in any event face a limited prospect of meaningful market entry into China given the lack of obvious candidates for partnership.

India: From software to hardware

With experience of over 20 years in attracting FDI, China today is one of the global centres for telecom equipment and handset manufacturing. A growing amount of design and R&D work for the global market is being conducted in China.

In addition to attracting major multinationals, China has in recent years seen the emergence of domestic companies on the global scene. Both Huawei and ZTE have switched their primary focus from domestic to overseas markets. Huawei generated 62 per cent of sales overseas in the first half of 2005. In 2004, Huawei's exports exceeded $2 billion. ZTE saw sales of 39 per cent overseas in 2004.

By contrast, India has had to rely to date overwhelmingly on imported equipment to build out its networks. This situation is not seen as sustainable. Dayanidhi Maran, the Indian minister for communications and information technology, has stated that "if we are going to add another 150 million subscribers by 2007, we cannot depend entirely on imports of equipment... We need the equipment to be manufactured in our country.

This opens the page on the next chapter in India's telecom development – the increase in multinational vendor activity. Alcatel has invested over $600 million and recently announced a broadband wireless R&D centre in Chennai. Ericsson's Jaipur plant started operations in February this year. Motorola is building a factory in India and basing its global "growth markets" division in India. Nokia is establishing its tenth global handset manufacturing base in Chennai, which will employ 2,000 people. Siemens has an R&D centre in Bangalore and a plant in Kolkata. LG manufactures handsets in Pune and plans to invest $60 million by 2010. Samsung entered India in 1997 and now produces most handsets locally, and maintains R&D centres in Bangalore and Noida.

Huawei has a small presence but plans for much more with a $100 million investment in a manufacturing and R&D centre in Bangalore. ZTE opened a handset manufacturing factory in Pune in March this year.

India's experience in manufacturing differs fundamentally from China's in that vendors came first for R&D, and second to manufacture and serve the local market. In the case of China, vendors were initially attracted by low-cost manufacturing and only subsequently to the promise of the domestic market and the R&D potential. Whatever the sequencing, India now has an opportunity to capitalise on its science and engineering skills and harness the appeal of its own market.

Critical to India's success in these efforts will be to provide the infrastructure – power, electricity, transportation – for a viable domestic equipment sector to be established. With its eyes firmly fixed on its neighbour to the north-east, this is a challenge that India is not willingly going to fail to meet.

- Most Viewed

- Most Rated

- Most Shared

- Related Articles

- Manufacturing Hub: India emerges as a ke...

- TRAI performance indicator report for Se...

- Prashant Singhal, partner, telecom indus...

- 2G spectrum scam: continuing controversy

- An Eventful Year: Telecom highlights of ...

- Telecom Round Table: TRAI’s spectrum p...

- Manufacturing Hub: TRAI recommends indig...

- Linking Up: ITIL to merge with Ascend

- High Speed VAS - Killer applications w...

- Bharti Airtel seals deal with Zain - Zai...